|  |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

|

Mutt, a worker in the lead mines, wanted his son to become a major leaguer and trained him as a switch-hitter. The righthanded Mutt and the lefthanded Charles Mantle, Mick's grandfather, took turns throwing to the youngster, and his swing developed from both sides of the plate.

While a high school sophomore, Mantle was kicked in his left shin during a football practice. The leg swelled and his temperature rose to 104 degrees. He had osteomyelitis, an inflammatory disease of the bone. Amputation was a consideration, but his mother transferred him to another hospital, and the leg was saved thanks to a new drug, penicillin.

After graduating from high school in 1949, the Yankees signed him, in scout Tom Greenwade's 1947 Oldsmobile, for a reported $1,100 bonus. Less than two years later, the 19-year-old Mantle, who was error-prone as a minor-league shortstop, was playing rightfield for the Yankees, right next to the great DiMaggio in center.

"He was a real country boy, all shy and embarrassed," pitcher Whitey Ford said. "He arrived with a straw suitcase and two pairs of slacks and one blue sports jacket that probably cost about eight dollars."

Mantle wasn't ready for "The Show," and was returned to the minors in July. After hitting .361 in 166 at-bats, he was back with New York to stay. He was given No. 7, instead of the No. 6 he wore on his first tour, and finished his rookie season with a .267 average and 13 homers. In Game Two of the 1951 World Series, chasing a fly ball hit by Mays and caught by DiMaggio, Mantle's spikes caught in a drainpipe covering. He tore up his right knee, and he never would play another pain-free game.

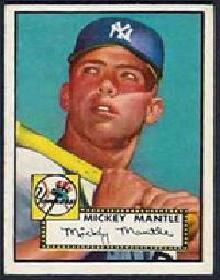

The next year, with DiMaggio's retirement, Mantle moved to centerfield. From 1952-60, he averaged 34 homers and 97 RBI. Four times he won home-run titles and in 1956 and 1957 he was voted MVP. (He would win a third in 1962.) Off the diamond, Mantle wasn't nearly as outstanding, frequently spurning kids who wanted his autograph or reporters who sought an interview.

Two home runs deserve special mention. There was his 565-foot blast off lefthander Chuck Stobbs in Washington in 1953, the first of the tape-measure homers. And in 1956 he missed by 18 inches from hitting the first ball out of Yankee Stadium, when his prodigious drive off righthander Pedro Ramos struck the top of the rightfield upper-deck facade.

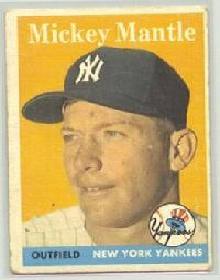

Ruth's record of 60 homers faced a two-pronged assault in 1961. Fans rooted against Roger Maris, and they urged Mantle on. But Maris broke the record with 61, while injury and illness halted Mantle's pursuit. He had to settle for 54, a career best and the most ever for a switch-hitter.

"I couldn't do anything wrong after Roger beat me," Mantle said. "I became the underdog; they hated him and liked me. Everywhere I went I got standing ovations. It was a lot better than having them boo you."

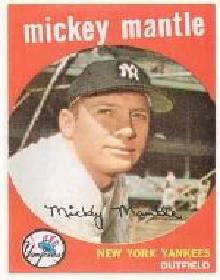

Injuries and drinking contributed to Mantle's slide in his final four years (1965-68). Batting .255, .288, .245 and .237, his lifetime average dropped to .298. "Falling under .300 was the biggest disappointment of my career," said Mantle, whose Hall of Fame career ended at age 36.

Mantle became more fan-friendly in retirement, and prospered in an era of nostalgia, earning money at card shows and allowing his name to be used in business ventures. A directionless Mantle kept on drinking. For more than 40 years he left empty glasses before he checked into the Betty Ford Clinic in 1994.

The next year, he had a liver transplant. It didn't work. Mantle died of cancer at 63 on Aug. 13, 1995 in Dallas.

"He was a presence in our lives -- a fragile hero to whom we had an emotional attachment so strong and lasting that it defied logic," said announcer Bob Costas in his eulogy to the Mick.

|  |  |  |  |  |  |