KENNEDY, JOHN F.

On November 22, 1963, when he was hardly past his first thousand days in office, John Fitzgerald Kennedy was killed by an assassin's bullets as his motorcade wound through Dallas, Texas. Kennedy was the youngest man elected President; he was the youngest to die.

Of Irish descent, he was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, on May 29, 1917. Graduating from Harvard in 1940, he entered the Navy. In 1943, when his PT boat was rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer, Kennedy, despite grave injuries, led the survivors through perilous waters to safety.

Back from the war, he became a Democratic Congressman from the Boston area, advancing in 1953 to the Senate. He married Jacqueline Bouvier on September 12, 1953. In 1955, while recuperating from a back operation, he wrote Profiles in Courage, which won the Pulitzer Prize in history.

In 1956 Kennedy almost gained the Democratic nomination for Vice President, and four years later was a first-ballot nominee for President. Millions watched his television debates with the Republican candidate, Richard M. Nixon. Winning by a narrow margin in the popular vote, Kennedy became the first Roman Catholic President.

His Inaugural Address offered the memorable injunction: "Ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country." As President, he set out to redeem his campaign pledge to get America moving again. His economic programs launched the country on its longest sustained expansion since World War II; before his death, he laid plans for a massive assault on persisting pockets of privation and poverty.

Responding to ever more urgent demands, he took vigorous action in the cause of equal rights, calling for new civil rights legislation. His vision of America extended to the quality of the national culture and the central role of the arts in a vital society.

He wished America to resume its old mission as the first nation dedicated to the revolution of human rights. With the Alliance for Progress and the Peace Corps, he brought American idealism to the aid of developing nations. But the hard reality of the Communist challenge remained.

Shortly after his inauguration, Kennedy permitted a band of Cuban exiles, already armed and trained, to invade their homeland. The attempt to overthrow the regime of Fidel Castro was a failure. Soon thereafter, the Soviet Union renewed its campaign against West Berlin. Kennedy replied by reinforcing the Berlin garrison and increasing the Nation's military strength, including new efforts in outer space. Confronted by this reaction, Moscow, after the erection of the Berlin Wall, relaxed its pressure in central Europe.

Instead, the Russians now sought to install nuclear missiles in Cuba. When this was discovered by air reconnaissance in October 1962, Kennedy imposed a quarantine on all offensive weapons bound for Cuba. While the world trembled on the brink of nuclear war, the Russians backed down and agreed to take the missiles away. The American response to the Cuban crisis evidently persuaded Moscow of the futility of nuclear blackmail.

Kennedy now contended that both sides had a vital interest in stopping the spread of nuclear weapons and slowing the arms race--a contention which led to the test ban treaty of 1963. The months after the Cuban crisis showed significant progress toward his goal of "a world of law and free choice, banishing the world of war and coercion." His administration thus saw the beginning of new hope for both the equal rights of Americans and the peace of the world.

INAUGURAL ADDRESS

LINCOLN, ABRAHAM

Lincoln warned the South in his Inaugural Address: "In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you.... You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to preserve, protect and defend it."

Lincoln thought secession illegal, and was willing to use force to defend Federal law and the Union. When Confederate batteries fired on Fort Sumter and forced its surrender, he called on the states for 75,000 volunteers. Four more slave states joined the Confederacy but four remained within the Union. The Civil War had begun.

The son of a Kentucky frontiersman, Lincoln had to struggle for a living and for learning. Five months before receiving his party's nomination for President, he sketched his life:

"I was born Feb. 12, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky. My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguished families--second families, perhaps I should say. My mother, who died in my tenth year, was of a family of the name of Hanks.... My father ... removed from Kentucky to ... Indiana, in my eighth year.... It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals still in the woods. There I grew up.... Of course when I came of age I did not know much. Still somehow, I could read, write, and cipher ... but that was all."

Lincoln made extraordinary efforts to attain knowledge while working on a farm, splitting rails for fences, and keeping store at New Salem, Illinois. He was a captain in the Black Hawk War, spent eight years in the Illinois legislature, and rode the circuit of courts for many years. His law partner said of him, "His ambition was a little engine that knew no rest."

He married Mary Todd, and they had four boys, only one of whom lived to maturity. In 1858 Lincoln ran against Stephen A. Douglas for Senator. He lost the election, but in debating with Douglas he gained a national reputation that won him the Republican nomination for President in 1860.

As President, he built the Republican Party into a strong national organization. Further, he rallied most of the northern Democrats to the Union cause. On January 1, 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation that declared forever free those slaves within the Confederacy.

Lincoln never let the world forget that the Civil War involved an even larger issue. This he stated most movingly in dedicating the military cemetery at Gettysburg: "that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain--that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom--and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

Lincoln won re-election in 1864, as Union military triumphs heralded an end to the war. In his planning for peace, the President was flexible and generous, encouraging Southerners to lay down their arms and join speedily in reunion.

The spirit that guided him was clearly that of his Second Inaugural Address, now inscribed on one wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D. C.: "With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds. "

On Good Friday, April 14, 1865, Lincoln was assassinated at Ford's Theatre in Washington by John Wilkes Booth, an actor, who somehow thought he was helping the South. The opposite was the result, for with Lincoln's death, the possibility of peace with magnanimity died.

FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS

SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS

MADISON, JAMES

At his inauguration, James Madison, a small, wizened man, appeared old and worn; Washington Irving described him as "but a withered little apple-John." But whatever his deficiencies in charm, Madison's buxom wife Dolley compensated for them with her warmth and gaiety. She was the toast of Washington.

Born in 1751, Madison was brought up in Orange County, Virginia, and attended Princeton (then called the College of New Jersey). A student of history and government, well-read in law, he participated in the framing of the Virginia Constitution in 1776, served in the Continental Congress, and was a leader in the Virginia Assembly.

When delegates to the Constitutional Convention assembled at Philadelphia, the 36-year-old Madison took frequent and emphatic part in the debates.

Madison made a major contribution to the ratification of the Constitution by writing, with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, the Federalist essays. In later years, when he was referred to as the "Father of the Constitution," Madison protested that the document was not "the off-spring of a single brain," but "the work of many heads and many hands."

In Congress, he helped frame the Bill of Rights and enact the first revenue legislation. Out of his leadership in opposition to Hamilton's financial proposals, which he felt would unduly bestow wealth and power upon northern financiers, came the development of the Republican, or Jeffersonian, Party.

As President Jefferson's Secretary of State, Madison protested to warring France and Britain that their seizure of American ships was contrary to international law. The protests, John Randolph acidly commented, had the effect of "a shilling pamphlet hurled against eight hundred ships of war."

Despite the unpopular Embargo Act of 1807, which did not make the belligerent nations change their ways but did cause a depression in the United States, Madison was elected President in 1808. Before he took office the Embargo Act was repealed.

During the first year of Madison's Administration, the United States prohibited trade with both Britain and France; then in May, 1810, Congress authorized trade with both, directing the President, if either would accept America's view of neutral rights, to forbid trade with the other nation.

Napoleon pretended to comply. Late in 1810, Madison proclaimed non-intercourse with Great Britain. In Congress a young group including Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, the "War Hawks," pressed the President for a more militant policy.

The British impressment of American seamen and the seizure of cargoes impelled Madison to give in to the pressure. On June 1, 1812, he asked Congress to declare war.

The young Nation was not prepared to fight; its forces took a severe trouncing. The British entered Washington and set fire to the White House and the Capitol.

But a few notable naval and military victories, climaxed by Gen. Andrew Jackson's triumph at New Orleans, convinced Americans that the War of 1812 had been gloriously successful. An upsurge of nationalism resulted. The New England Federalists who had opposed the war--and who had even talked secession--were so thoroughly repudiated that Federalism disappeared as a national party.

In retirement at Montpelier, his estate in Orange County, Virginia, Madison spoke out against the disruptive states' rights influences that by the 1830's threatened to shatter the Federal Union. In a note opened after his death in 1836, he stated, "The advice nearest to my heart and deepest in my convictions is that the Union of the States be cherished and perpetuated."

FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS

SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS

MC KINLEY, WILLIAM

At the 1896 Republican Convention, in time of depression, the wealthy Cleveland businessman Marcus Alonzo Hanna ensured the nomination of his friend William McKinley as "the advance agent of prosperity." The Democrats, advocating the "free and unlimited coinage of both silver and gold"--which would have mildly inflated the currency--nominated William Jennings Bryan.

While Hanna used large contributions from eastern Republicans frightened by Bryan's views on silver, McKinley met delegations on his front porch in Canton, Ohio. He won by the largest majority of popular votes since 1872.

Born in Niles, Ohio, in 1843, McKinley briefly attended Allegheny College, and was teaching in a country school when the Civil War broke out. Enlisting as a private in the Union Army, he was mustered out at the end of the war as a brevet major of volunteers. He studied law, opened an office in Canton, Ohio, and married Ida Saxton, daughter of a local banker.

At 34, McKinley won a seat in Congress. His attractive personality, exemplary character, and quick intelligence enabled him to rise rapidly. He was appointed to the powerful Ways and Means Committee. Robert M. La Follette, Sr., who served with him, recalled that he generally "represented the newer view," and "on the great new questions .. was generally on the side of the public and against private interests."

During his 14 years in the House, he became the leading Republican tariff expert, giving his name to the measure enacted in 1890. The next year he was elected Governor of Ohio, serving two terms.

When McKinley became President, the depression of 1893 had almost run its course and with it the extreme agitation over silver. Deferring action on the money question, he called Congress into special session to enact the highest tariff in history.

In the friendly atmosphere of the McKinley Administration, industrial combinations developed at an unprecedented pace. Newspapers caricatured McKinley as a little boy led around by "Nursie" Hanna, the representative of the trusts. However, McKinley was not dominated by Hanna; he condemned the trusts as "dangerous conspiracies against the public good."

Not prosperity, but foreign policy, dominated McKinley's Administration. Reporting the stalemate between Spanish forces and revolutionaries in Cuba, newspapers screamed that a quarter of the population was dead and the rest suffering acutely. Public indignation brought pressure upon the President for war. Unable to restrain Congress or the American people, McKinley delivered his message of neutral intervention in April 1898. Congress thereupon voted three resolutions tantamount to a declaration of war for the liberation and independence of Cuba.

In the 100-day war, the United States destroyed the Spanish fleet outside Santiago harbor in Cuba, seized Manila in the Philippines, and occupied Puerto Rico.

"Uncle Joe" Cannon, later Speaker of the House, once said that McKinley kept his ear so close to the ground that it was full of grasshoppers. When McKinley was undecided what to do about Spanish possessions other than Cuba, he toured the country and detected an imperialist sentiment. Thus the United States annexed the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico.

In 1900, McKinley again campaigned against Bryan. While Bryan inveighed against imperialism, McKinley quietly stood for "the full dinner pail."

His second term, which had begun auspiciously, came to a tragic end in September 1901. He was standing in a receiving line at the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition when a deranged anarchist shot him twice. He died eight days later.

FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS

SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS

MONROE, JAMES

On New Year's Day, 1825, at the last of his annual White House receptions, President James Monroe made a pleasing impression upon a Virginia lady who shook his hand:

"He is tall and well formed. His dress plain and in the old style.... His manner was quiet and dignified. From the frank, honest expression of his eye ... I think he well deserves the encomium passed upon him by the great Jefferson, who said, 'Monroe was so honest that if you turned his soul inside out there would not be a spot on it.' "

Born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1758, Monroe attended the College of William and Mary, fought with distinction in the Continental Army, and practiced law in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

As a youthful politician, he joined the anti-Federalists in the Virginia Convention which ratified the Constitution, and in 1790, an advocate of Jeffersonian policies, was elected United States Senator. As Minister to France in 1794-1796, he displayed strong sympathies for the French cause; later, with Robert R. Livingston, he helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase.

His ambition and energy, together with the backing of President Madison, made him the Republican choice for the Presidency in 1816. With little Federalist opposition, he easily won re-election in 1820.

Monroe made unusually strong Cabinet choices, naming a Southerner, John C. Calhoun, as Secretary of War, and a northerner, John Quincy Adams, as Secretary of State. Only Henry Clay's refusal kept Monroe from adding an outstanding Westerner.

Early in his administration, Monroe undertook a goodwill tour. At Boston, his visit was hailed as the beginning of an "Era of Good Feelings." Unfortunately these "good feelings" did not endure, although Monroe, his popularity undiminished, followed nationalist policies.

Across the facade of nationalism, ugly sectional cracks appeared. A painful economic depression undoubtedly increased the dismay of the people of the Missouri Territory in 1819 when their application for admission to the Union as a slave state failed. An amended bill for gradually eliminating slavery in Missouri precipitated two years of bitter debate in Congress.

The Missouri Compromise bill resolved the struggle, pairing Missouri as a slave state with Maine, a free state, and barring slavery north and west of Missouri forever.

In foreign affairs Monroe proclaimed the fundamental policy that bears his name, responding to the threat that the more conservative governments in Europe might try to aid Spain in winning back her former Latin American colonies. Monroe did not begin formally to recognize the young sister republics until 1822, after ascertaining that Congress would vote appropriations for diplomatic missions. He and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams wished to avoid trouble with Spain until it had ceded the Floridas, as was done in 1821.

Great Britain, with its powerful navy, also opposed reconquest of Latin America and suggested that the United States join in proclaiming "hands off." Ex-Presidents Jefferson and Madison counseled Monroe to accept the offer, but Secretary Adams advised, "It would be more candid ... to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war."

p>

Monroe accepted Adams's advice. Not only must Latin America be left alone, he warned, but also Russia must not encroach southward on the Pacific coast. ". . . the American continents," he stated, "by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European Power." Some 20 years after Monroe died in 1831, this became known as the Monroe Doctrine.

FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS

ECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS

NIXON, RICHARD M.

Reconciliation was the first goal set by President Richard M. Nixon. The Nation was painfully divided, with turbulence in the cities and war overseas. During his Presidency, Nixon succeeded in ending American fighting in Viet Nam and improving relations with the U.S.S.R. and China. But the Watergate scandal brought fresh divisions to the country and ultimately led to his resignation.

His election in 1968 had climaxed a career unusual on two counts: his early success and his comeback after being defeated for President in 1960 and for Governor of California in 1962.

Born in California in 1913, Nixon had a brilliant record at Whittier College and Duke University Law School before beginning the practice of law. In 1940, he married Patricia Ryan; they had two daughters, Patricia (Tricia) and Julie. During World War II, Nixon served as a Navy lieutenant commander in the Pacific.

On leaving the service, he was elected to Congress from his California district. In 1950, he won a Senate seat. Two years later, General Eisenhower selected Nixon, age 39, to be his running mate.

As Vice President, Nixon took on major duties in the Eisenhower Administration. Nominated for President by acclamation in 1960, he lost by a narrow margin to John F. Kennedy. In 1968, he again won his party's nomination, and went on to defeat Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey and third-party candidate George C. Wallace.

His accomplishments while in office included revenue sharing, the end of the draft, new anticrime laws, and a broad environmental program. As he had promised, he appointed Justices of conservative philosophy to the Supreme Court. One of the most dramatic events of his first term occurred in 1969, when American astronauts made the first moon landing.

Some of his most acclaimed achievements came in his quest for world stability. During visits in 1972 to Beijing and Moscow, he reduced tensions with China and the U.S.S.R. His summit meetings with Russian leader Leonid I. Brezhnev produced a treaty to limit strategic nuclear weapons. In January 1973, he announced an accord with North Viet Nam to end American involvement in Indochina. In 1974, his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, negotiated disengagement agreements between Israel and its opponents, Egypt and Syria.

In his 1972 bid for office, Nixon defeated Democratic candidate George McGovern by one of the widest margins on record.

Within a few months, his administration was embattled over the so-called "Watergate" scandal, stemming from a break-in at the offices of the Democratic National Committee during the 1972 campaign. The break-in was traced to officials of the Committee to Re-elect the President. A number of administration officials resigned; some were later convicted of offenses connected with efforts to cover up the affair. Nixon denied any personal involvement, but the courts forced him to yield tape recordings which indicated that he had, in fact, tried to divert the investigation.

As a result of unrelated scandals in Maryland, Vice President Spiro T. Agnew resigned in 1973. Nixon nominated, and Congress approved, House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford as Vice President.

Faced with what seemed almost certain impeachment, Nixon announced on August 8, 1974, that he would resign the next day to begin "that process of healing which is so desperately needed in America."

In his last years, Nixon gained praise as an elder statesman. By the time of his death on April 22, 1994, he had written numerous books on his experiences in public life and on foreign policy.

FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS

SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS

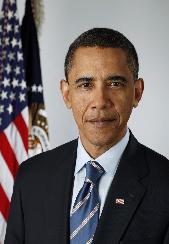

OBAMA, BARAK

Illinois voters sent a Democratic newcomer, Barack Obama, to one of the state's two seats in the U.S. Senate in 2004. Obama's landslide victory in Illinois was significant on several fronts. Firstly, he became the Senate's only African American lawmaker when he was sworn into office in January 2005, and just the third black U.S. senator to serve there since the 1880s. Moreover, Obama's political supporters came from a diverse range of racial and economic backgrounds, which is still relatively rare in American electoral politics—traditionally, black candidates have not done very well in voting precincts where predominantly non-minority voters go to the polls. Even before his Election Day victory, Obama emerged as the new star of the Democratic Party after delivering the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention in Boston, Massachusetts that summer. His stirring speech, in which he urged a united, not a divided, American union, prompted political commentators to predict he might become the first African American elected to the White House.

Obama is actually of mixed heritage. He was born in 1961 in Honolulu, Hawaii, where his parents had met at the University of Hawaii's Manoa campus. His father, Barack Sr., was from Kenya and entered the University of Hawaii as its first-ever student from an African country. He was a member of Kenya's Luo ethnic group, many of whom played a key role in that country's struggle for independence in the 1950s. Obama's mother, Ann Durham, was originally from Kansas, where some of her ancestors had been anti-slavery activists in the 1800s. The marriage between Obama's parents was a short-lived one, however. In the early 1960s, interracial relationships were still quite rare in many parts of America, and even technically illegal in some states. The Durhams were accepting of Barack Sr., but his family in Kenya had a harder time with the idea of his marryinga white American woman. When Obama was two years old they divorced, and his father left Hawaii to enter Harvard University to earn a Ph.D. in economics. The two Baracks met again only once, when Obama was ten, though they did write occasionally. Barack Sr. eventually returned to Kenya and died in a car accident there in the early 1980s.

Obama's mother remarried a man from Indonesia who worked in the oil industry, and when Obama was six they moved there. The family lived near the capital of Jakarta, where his half-sister Maya was born. At the age of ten, Obama returned to Hawaii and lived with his maternal grandparents; later his mother and sister returned as well. Called "Barry" by his family and friends, he was sent to a prestigious private academy in Honolulu, the Punahou School, where he was one of just a handful of black students. Obama recalled feeling conflicted "In no other country on earth is my story even possible." about his mixed heritage in his teen years. Outside the house, he was considered African American, but the only family he knew was his white one at home. For a time, he loafed and let his grades slip; instead of studying, he spent hours on the basketball court with his friends, and has admitted that there was a time when he experimented with drugs, namely marijuana and cocaine. "I was affected by the problems that I think a lot of young African American teens have," he reflected in an interview with Kenneth Meeks for Black Enterprise. "They feel that they need to rebel against society as a way of proving their blackness. And often, this results in self-destructive behavior." Excels at Harvard Law School

Obama graduated from Punahou and went on to Occidental College in Los Angeles, where he decided to get serious about his studies. Midway through, he transferred to the prestigious Columbia University in New York City. He also began to explore his African roots and not long after his father's death traveled to meet his relatives in Kenya for the first time. After he earned his undergraduate degree in political science, he became a community organizer in Harlem—but quickly realized he could not afford to live in the city with a job that paid so little. Instead, he moved to Chicago to work for a church-based social-services organization there. The group was active on the city's South Side, one of America's most impoverished urban communities. Feeling it was time to move on, Obama applied to and was accepted at Harvard Law School, one of the top three law schools in the United States. In 1990, he was elected president of the Harvard Law Review journal. He was the first African American to serve in the post, which virtually assured him of any career path he chose after graduation. But Obama declined the job offers from top Manhattan law firms, with their starting salaries that neared the $100,000-a-year range, in order to return to Chicago and work for a small firm that specialized in civil-rights law. This was an especially unglamorous and modest-paying field of law, for it involved defending the poor and the marginalized members of society in housing and employment discrimination cases. Obama also had another reason for returning to Chicago: During his Harvard Law School years, he took a job as a summer associate at a Chicago firm, and the attorney assigned to mentor him was also a Harvard Law graduate, Michelle Robinson. The two began dating and were married in 1992. Robinson came from a working-class black family and grew up on the South Side; her brother had excelled at basketball and went to Princeton University, and she followed him there for her undergraduate degree. Obama also considered Chicago a place from which he could launch a political career, and he became active in a number of projects in addition to his legal cases at work and another job he held teaching classes at the University of Chicago Law School. He worked on a local voter-registration drive, for example, that registered thousands of black voters in Chicago; the effort was said to have helped Bill Clinton (1946–) win the state in his successful bid for the White House in

1992.

Obama's time at the Law Review had netted him an offer to write a book. The result was Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance, published by Times Books in 1995. The work merited some brief but mostly complimentary reviews in the press. Obama, however, was not hoping for a career as an author: he decided to run for a seat in the Illinois state senate. He ran from his home district of Hyde Park, the neighborhood surrounding the elite University of Chicago on the South Side. Though Hyde Park is similar to many American college towns, with well-kept homes and upscale businesses, the surrounding neighborhood is a more traditionally urban one, with higher levels of both crime and unemployment.

Obama won that 1996 election and went on to an impressive career in the Senate chambers in Springfield, the state capital. He championed a bill that gave tax breaks to low-income families, worked to expand a state health-insurance program for uninsured children, and wrote a bill that required law enforcement officials in every community to begin keeping track of their traffic stops and noting the race of the driver. This controversial bill, which passed thanks to Obama's determined effort to find support from both political parties in the state Senate, was aimed at reducing incidents of alleged racial profiling, or undue suspicion turned upon certain minority or ethnic groups by police officers on patrol. He also won passage of another important piece of legislation that required police to videotape homicide confessions. Obama made his first bid for U.S. Congress in 2000, when he challenged a well-known black politician and former Chicago City Council member, Bobby Rush (1946–), for his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Rush was a former black Senator

Barack Obama became the fifth African American senator in U.S. history in 2005. He was only the third elected since the end of the Reconstruction, the period immediately following the end of the American Civil War (1861–65; a war between the Union [the North], who were opposed to slavery, and the Confederacy [the South], who were in favor of slavery). During the Reconstruction Era, federal troops occupied the defeated Southern states and, along with transplanted government officials, one of their duties was to make sure that newly freed slaves were allowed to vote fairly and freely in elections. Before 1913 and the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, members of the U.S. Senate were not directly elected by voters in most states, however. Instead they were elected by legislators in the state assemblies, or appointed by the governor. Still, because of the Reconstruction Era reforms, many blacks were elected to the state legislatures that sent senators to Washington. In 1870, the Mississippi state legislature made Hiram Rhoades Revels (1827–1901) the state's newest senator and the first black ever to serve in the U.S. Senate. Revels was a free-born black from North Carolina and a distinguished minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church who had raised two black regiments that fought on the Union side during the Civil War. He served in the Senate for one year.

In 1875, Mississippi lawmakers sent Blanche K. Bruce (1841–1898) to the U.S. Senate. A former slave from Virginia, Bruce was a teacher and founder of the first school for blacks in the state of Missouri. After the end of the Civil War, he headed south to take part in the Reconstruction Era. He won election to local office as a Republican, and in 1875 lawmakers sent him to the U.S. Senate. He served the full six-year term. In 1881, he was appointed a U.S. Treasury official, and his signature was the first from an African American to appear on U.S. currency.

Nearly a hundred years passed before another African American was elected to the Senate, and this came by statewide vote. Edward William Brooke III (1919–), a Republican from Massachusetts, was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1966 and served two terms. In 1992 another Illinois Democrat, Carol Moseley Braun (1947–), became the first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Senate.

Barack Obama won his bid for the Senate by a large margin, taking 70 percent of the Illinois vote, thus becoming one of the youngest members of the U.S. Senate when he was sworn into office in January 2005.

A few years later, Obama decided to run for a seat in the U.S. Senate when Illinois Republican Peter G. Fitzgerald (1960–) announced he would retire. Some of Obama's supporters thought he was aiming too high, but this time he beat out six other Democratic challengers in the primary with 53 percent of the vote. Suddenly, state and even national Democratic Party leaders began taking him and his Senate campaign seriously. In the primary, he had managed to do what few African American politicians had ever done: record an impressive number of votes from precincts that had a predominantly white population. In his 2004 Senate race, Obama faced a tough Republican challenger, however: a former investment banker turned parochial-school (school supported by a church parish) teacher named Jack Ryan (1960–). Ryan was blessed with television-actor good looks and had even once been married to Boston Public star Jeri Ryan (1968–). But Jack Ryan was, like one of Obama's earlier primary opponents, derailed by allegations about his personal life. Chicago news outlets publicized Ryan's divorce documents from 1999, which revealed one or two incidents that seemed distinctly at odds with a Republican "family values" platform. Ryan dropped out of the race, but the Republican National Party quickly brought in talk-show host Alan Keyes (1950–), who changed his home address from Maryland to Illinois to run against Obama. Keyes was a conservative black Republican who twice had made a bid for the White House, but he worried some voters with his strong statements against homosexuality.

Obama, by contrast, was winning public-opinion polls among every demographic group that pollsters asked. He was even greeted with rock-star type cheers in rural Illinois farm towns. Many of these small-town voters recognized that the manufacturing operations of many U.S. industries were rapidly being moved overseas thanks to free-trade agreements that eliminated tariffs (taxes) and trade barriers between the United States and Mexico; another free-trade agreement was in the works for Central America. The result was a dramatic decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs. Obama's campaign pledged to stop the outsourcing of such jobs to overseas facilities. But Obama suddenly found himself in the national spotlight, when John Kerry (1943–), expected to win the Democratic Party's nomination for president at the Democratic National Convention in July 2004, asked Obama to deliver the convention's keynote address. The keynote speech is expected to set the tone of the political campaign, and those chosen to give face tremendous expectations. "That makes my life poorer"

Obama did not disappoint that evening. His speech, which he wrote himself and titled "The Audacity of Hope," was stirring and eloquent, and quickly dubbed by political analysts to be one of the best convention keynote addresses of the modern era. He earned several standing ovations during it, and Obama's confident, assured tone was broadcast to the rest of the nation. Cameras occasionally scanned the crowd to show tears on the faces of delegates. Obama praised Kerry's values and experience, and he reminded delegates and the national television audience that the country's strength came from unity, not division—that Americans had created a thriving nation out of many diverse ethnic groups and ideologies in its 228-year history. Economic policies aimed at providing a better life for everyone, not just a privileged few, was the American way, he said. "If there's a senior citizen somewhere who can't pay for her prescription and has to choose between medicine and the rent, that makes my life poorer, even if it's not my grandmother," he told the crowd. "If there's an Arab American family being rounded up without benefit of an attorney or due process, that threatens my civil liberties. It's that fundamental belief—I am my brother's keeper, I am my sister's keeper—that makes this country work."

Obama's speech, analysts said almost immediately, struck a hopeful, healing tone for a drastically divided nation and what had become a bitter, insult-heavy presidential contest. Obama, asserted Time 's Amanda Ripley, "described a country that America wants very badly to be: a country not pockmarked by racism and fear or led by politicians born into privilege and coached into automatons [robotic behavior]." Others called it one of the best political speeches of the century. Some newspaper and magazine editorial writers predicted that the rising star from Illinois would emerge a strong leader in the Democratic Party over the next few years, and could even run for president in 2012 or 2016. Obama won his bid for the Senate a few months later by a large margin, taking 70 percent of the Illinois vote against just 27 percent for Keyes. At just forty-three years old, he became one of the youngest members of the U.S. Senate when he was sworn into office in January

2005.

The first major piece of legislation he introduced came two months later with the Higher Education Opportunity through Pell Grant Expansion Act of 2005 (HOPE Act). Its goal was increase the maximum amount that the federal government provides each student who receives need-based financial aid for college. In the 1970s and 1980s, Pell grants often covered nearly the entire tuition cost— excluding room, board, and books—at some state universities. But because they had failed to keep pace with risingtuition costs by 2005 they covered, on average, just 23 percent of the tuition at state schools.

Obama and his wife have two young daughters, Malia and Sasha

INAUGURAL ADDRESS