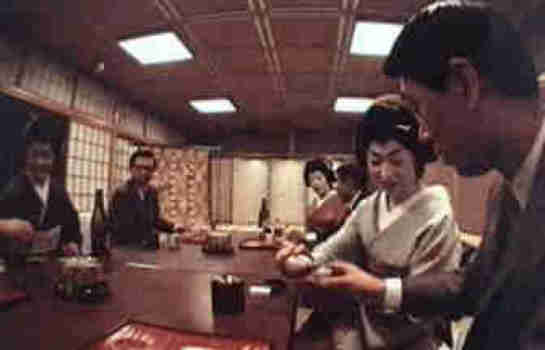

So it is with the geisha who, like the

swordsmith or kabuki actor or woodblock

artist or

even the sushi chef, must undergo

a long and trying apprenticeship before she

can officially attain the status of "geisha."

In early times, girls began this apprenticeship

while

still pre teens; however,today the age

for entering geisha training is fifteen.

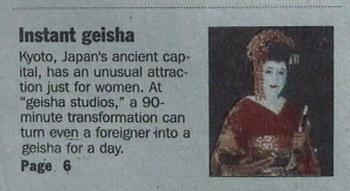

It may well be that geisha provide a comfortable

reminder for the human need

to remember the way things used to be. Women who pay a handsome sum to

stroll the streets

of Kyoto in the guise of geisha certainly

offer testimony to the

fascination and mystique that these women who "practice the arts" still

possess.

~NEXT~

~NEXT~