The saga of "Bunraku,"Japan's puppet theater, can be likened to the ebb and flow,

The saga of "Bunraku,"Japan's puppet theater, can be likened to the ebb and flow,

mountains and valleys, of any cultural art or even commercial enterprise. From its

early traditions of traveling tale spinners and puppeteers to a stylized dramatic

form, Japan's puppet theater has experienced these ups and downs. "The Puppet Theater of Japan"

"Bunraku" is a unique form of puppet theater found only in Japan with its roots

"The Puppet Theater of Japan"

"Bunraku" is a unique form of puppet theater found only in Japan with its roots

grounded in a long tradition of traveling story tellers ("joruri") and traveling

puppeteers ("ningyo" meaning doll). The merger in the late 1600's, of the story

teller and the puppeteer became known as "ningyo joruri," (puppet and story).

In 1684 Tatemoto Gidayu (1651-1714), a well known joruri chanter ("tayu"),

established a puppet theater in Osaka for the purpose of staging kingyo jurori

performances. With the help of a theater owner/promoter and Japan's most

famous playwright, Chikamatsu Manzaemon, the "Tatemotoza" theater

quickly became a success. Chikamatsu's stirring historical themes as well

as his dramatizations of individual struggles between the conflicting forces

of social obligations and human emotions ("ninjo" and "giri") found great

favor with Osaka's merchants and rising middle classes. Chikamatsu went

on to write more than one hundred plays for the Osaka theater, many

of which were also adapted for the kabuki stage.

The golden period of bunraku's popularity would be reached during the 1740's but then

it would enter a fifty year time of decline. Many of the best narrators, playwrights and

puppeteers had died, increasing competition from kabuki forced the closure of bunraku

venues and theater backers went bankrupt; however, the dawn of the new century would

see an upswing in bunraku's fortunes. In 1805, a jorui chanter from Awaji island, Uemura

Burakuken settled in Osaka with his puppeteering group and set up a theater there called

"Bunrakuza." It was at this juncture that the story and puppet dramas originally termed

"ningyo joruri" would hereafter be known as "Bunraku."

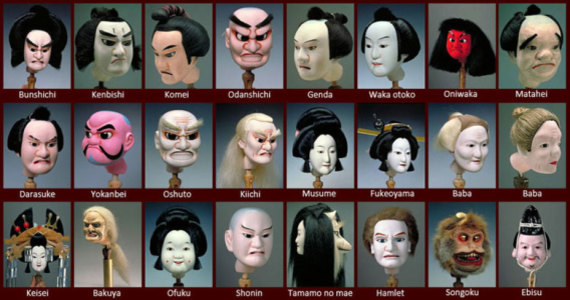

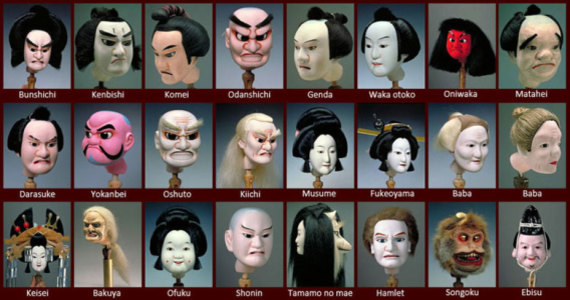

Bunraku puppets are large, usually one-half to two-thirds

Bunraku puppets are large, usually one-half to two-thirds

life size and are manipulated by three puppeteers.Unlike most puppet theaters where great pains are taken to hide the puppeteers

from the audience, the manipulators appear openly, in full view of the audience. The chief handler, meant to be seen and always visible to the audience operates

the head, moving the eyes, eyebrows, lips and fingers, and right hand. The two

helpers, dressed and hooded in black, masking themselves so as to be "invisible"

and not seen, operate the left hand and feet. Movements of the three manipulators

requires long training to perfect the synchronization of movement necessary

to portray the lifelike actions and emotions of the dolls.

Seated to the right of the stage on a slightly raised platform is a chanter ("tayu") who is the narrator and voice of all the puppets and three shamisen players who provide musical

background for the drama. The synchronization of all three elements, the puppets,

chanter and shamisen creates the dramatic, emotional force of the performance.

Japan for more than 250 years, under the the Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868) was

a military dictatorship with a rigid feudal class structure controlled by samurai lords.

This would all change in 1868 with the restoration of the Emperor Meiji (1868-1912)

ushering in an era of modernization and opening the country to western influence in

all sectors of society and government. Japan and the Japanese became enamored of

"things western." Changes came rapid fire, in politics, the military, education, industry,

foreign affairs and even clothing styles. "To be enlightened was to be Western!" This

of course did not bode well for the fortunes of bunraku as its struggle continued.

The Bunrakuza in Osaka was destroyed by bombing in 1945 and although rebuilt

the following year, the chaotic conditions at war's end, along with the problems of

rebuilding a nation, bunraku suffered an extremely hard time. It was hoped that

the creation of a National Theater in Tokyo in 1966 and the establishment of the

National Bunraku Theater in Osaka in 1984 would give new life to the struggling

art but the decline continued. Bunraku currently relies heavily on revenues from

the national theaters together with government sponsorship and subsidies from

the national as well as the Osaka prefectural and municipal governments.Although there have been occasional increases in its popularity and government

assistance has helped to bouy up its fortunes, the most serious problem facing

bunraku's continued existence rests in the replacement of skilled personnel.

Craftsmen who create the puppets and fashion the costumes are dying out

and not being replaced and the lengthy apprenticeship required to become

a puppet master ("omozukai"), to commit to "art for art's sake" has

very little appeal to today's young generation.

Omozukai Kiratake Kanjuro III has remarked that before an apprentice can

become a lead puppeteer he must spend ten years learning to control the legs,

another fifteen learning control of the left arm; twenty five years before he can

shed the black hood, show his face and move up to the head and right hand!

This problem is not unique to the highly stylized and tradition bound bunraku

but is shared by kabuki, noh and kyogen as well. Getting "new blood" out of

a recruitment pool that is far less responsive than ever before, together with

the fact that Japan's performing arts are male dominated reducing the pool

by half is certainly a formidable challenge! Perhaps more ominous, is the

fact that these conditions pose a very real future threat for practitioners

of Japan's highly respected and revered traditional arts.

~ BACK ~ ~ NEXT ~

~ NEXT ~

~ NEXT ~

~ NEXT ~