|

If the Kabuki theater with all its

pomp and pageantry, its

colorful costumes,

revolving stage and

violent actions and emotions could be called

the "yang"

of Japanese drama, then Noh surely

is its "yin" counterpart.

|

Noh drama, it is

said, originated with simple popular

folk dances and plays Unlike Kabuki, Noh plays are

performed on an almost bare stage,

that were performed at

Shinto festivals to pray to the gods for

abundant

harvests and to give thanks after the harvest.By the fourteenth century,

these

simple performances had developed into

symbolic

dances performed at the imperial

court in Nara.

open on

three sides, simple and plain having neither

a curtain nor

background scenery except for a

pine tree painted on the rear

wall.

|

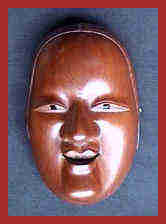

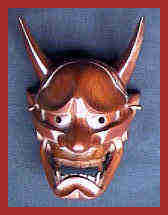

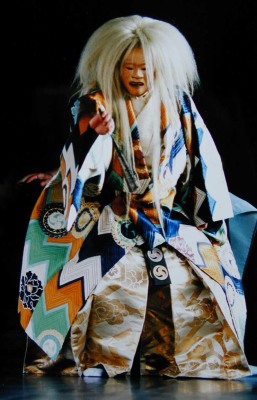

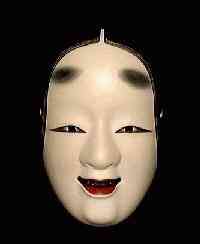

Two actors usually perform on stage, the protagonist, who is frequently

the spirit of a person tied to this earth by worldly desires but longing

for salvation and his assistant; both are elaborately costumed

and

wear masks. There

may also be two or three minor characters and

there is always a chorus, kneeling on the

right side of the stage,

reciting the

narrative and describing the changes of

scene. The

musical accompaniment is not music

in the western sense,

it is pure sound

provided by three drums and a

flute.

|

The plays are usually brief and several short

dramas are performed

at a single sitting.

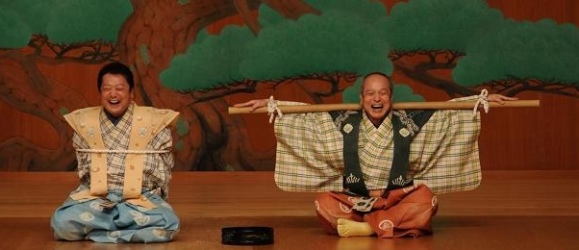

Interspersed between the Noh dramas are comic

skits known as "Kyogen ("crazy words") which

offer burlesques

of feudal society and

provide comic relief for the unremitting

gloom

that pervades nearly all of Noh. The broad and

slapstick humor of Kyogen often

depicts clever

servants outwitting their

samurai masters.

|

|

The principal actor's movements and gestures, however minute, are highly stylized,

formal and carefully

measured. Mime constitutes an important part

of the drama;

feelings are expressed in

symbolic gestures and movements. The

manipulation

of a fan can symbolize falling

leaves, rippling water or a rising moon;

weeping is expressed by raising a hand to the

eyes.

|

The aim of Noh is to express a desire or yearning, not for beauty, but for Although not specifically Zen

inspired, one observer has noted that Noh in a way is like a fermented bean concoction

the beauty we dream. The worth of the play then depends less upon the

truth or moral, but

upon the total effect of the beauty produced

- poetry.

Noh

offers an excellent example of the highly

refined and disciplined

spirit of Zen

aesthetics. Noh, although it cannot be

described as a

popular art among the Japanese

people as a whole, does have its

supporters

who, attend the theaters as connoisseurs with

script

in hand, following the actor's every

movement and word.

I have attended Noh

performances but must admit that

I prefer

Kyogen and find them a welcome relief!

("natto") that some Japanese simply love

while

others prefer to simply leave.

|

~NEXT~

~NEXT~