In the early years, the

interests of such acting groups seems to have

been more

in sex than in serious dramatic

performance. Alarmed by the immorality

of the

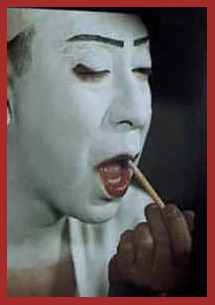

theater, the government banned all

women performers from

the stage in an effort

to safeguard the public's morals.

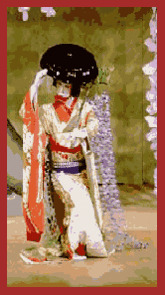

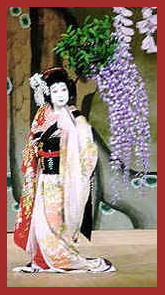

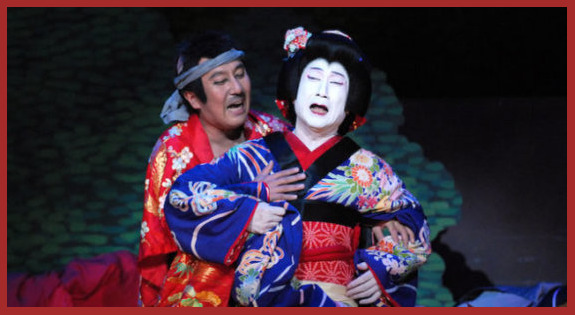

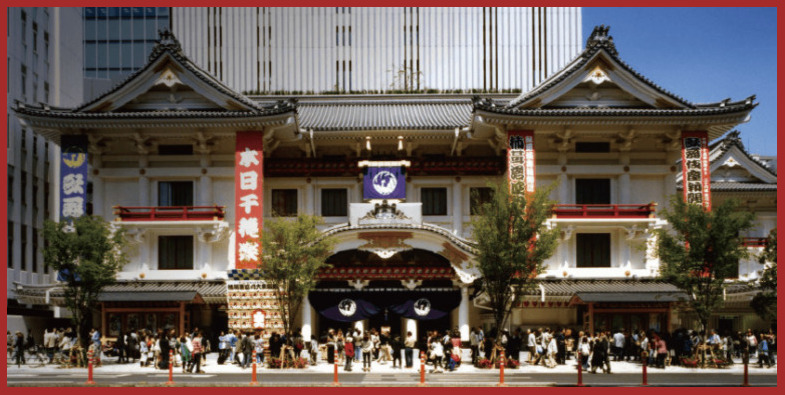

Kabuki was, in many ways, a child of the Genroku era,

when the

merchant class emerged as a strong

economic force in the urban

areas.Common

people soon became enamored of these dramas

with their gaudy and bright costumes, violent

actions and strong

emotional tension; the

colorful day-long performances attracted

all ranks of society, shop

keepers and merchants to samurai.

~NEXT~

~NEXT~