| ||||

mispronounced as often as are the women it

identifies, misunderstood. Pronounced "gay-sha,"

the word translates as "art person" or "person of

the arts" and that is simply what geisha are,

practitioners of arts that reach back in time

more than three centuries.

undergone rigorous training in music, dance,

calligraphy, the tea ceremony, as well as

conversational and social graces. Geisha

are skilled story tellers and, singers, as well

as proficient accompanists on their

three-stringed shamisen.

Tokugawa era, in the 17th century, when Japan

was at peace, isolated from the outside world

and when samurai and merchant had time

and wealth enough to indulge themselves

in the pleasures of the "floating world."

of the exotic, of fantasy in the very word, "geisha"

and the sound of it can still conjure up images

of a time long past; a time when when the

sounds of laughter and shamisen drifted

from the tea houses into the night air as

samurai strutted down the streets of Edo.

celebrations banging their drums, singing songs

and telling funny stories were men; gradually

however, women began appearing to

challenge the male entertainers and by

mid 17th century, female geisha had

attained a dominance which

soon became their monopoly.

women brought to the geisha scene served to

inspire countless musicians, poets and artists

who sought to capture the spirit and images

of the geisha's "willow world."

Japan has experienced in the last one hundred or

even fifty years, tradition remains a strong, persistent

ingredient within the base of all that is new.

So it is with the geisha who, like the

swordsmith

or kabuki actor or woodblock

artist or even the sushi

chef, must undergo

a long and trying apprenticeship

before she can officially attain the status of "geisha."

In early times, girls began this apprenticeship while

still pre teens; however,today the age

for

entering geisha training is fifteen.

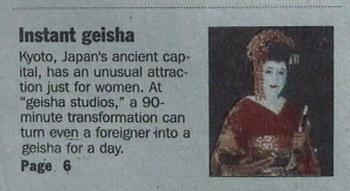

Unique hair styles, hair ornaments and stark white facial makeup gives the maiko the dream-like quality of a porcelain doll. Perhaps because they still lack the skills of their elder sisters, the maikos' appearance must rely more on outward showiness but, by the time they reach their early twenties, diligent and successful maiko are ready to put aside their doll like accouterments and take up the subtler shades of kimono and more sophisticated demeanor of "geisha."

were the trend setters of high fashion and good

taste but with the changes that have taken place

since then, that role has disappeared.

In the late

1970's, the number of registered geisha

fell to around 1,500 and today, there are

probably

fewer than a thousand women

practicing the

profession and lifestyle

of geisha.

and Pontocho districts geisha perform and

entertain their guests who usually have a long

relationship with the ochaya, as new customers

are rarely admitted without proper introduction.

As

in times long past, when geisha

helped

to soothe the worries and cares of

samurai and

merchant, the sounds of shamisen and song that fill

today's ochaya are a haunting reminder of tradition's

persistence.

Inside the teahouse of Gion or Pontocho,

it is now perhaps the tired businessman or

harried

politician who half fancies himself

as the bold

samurai of yore whose cares

are eased and ego

lifted by the lovely,

gentle geisha who fills his

sake cup and

sings only to him!

of geisha was provided by a recent article

that appeared in the travel section of

my Sunday newspaper.

The half

page story related the success of more

than forty shops in Kyoto catering to Western tourists

and Japanese women as well who pay $100 to $350

to be made up and attired

as maiko or geisha. For

a slight additional

fee, these "90 minute geisha" may

obtain photographs of themselves and stroll

around a

nearby temple ground reveling

in the spectacle of

camera hounds jostling to take their pictures. More

than 70,000 patrons each year avail themselves

of the

services of these "geisha studios"

contributing a not insubstantial boon

to the Kyoto economy.

each year, and fewer teenagers find such a

ritualized and rigorous life attractive, it would be

far too presumptuous, in light of their proven staying

power, to predict the geisha's disappearance

in the near future.

Geisha are a link with the past

and Japanese are reluctant to abandon such

ties.

If the number of paying customers at the

busy

"geisha studios" is any indication, geisha are still

respected, imitated and even admired

for their

commitment to a way of life that is

admittedly

out of tune with today's Japan.

It may well be that geisha provide a comfortable

reminder

for the human need to remember the way things used to be. Women

who pay a handsome sum to stroll the streets

of Kyoto in

the guise of geisha certainly

offer testimony to the

fascination and mystique that these women

who "practice the arts" still

possess.

~NEXT~

~NEXT~