|

If the Kabuki theater with all its

pomp and

pageantry, its

colorful costumes, revolving stage

and

violent actions and emotions could be

called

the "yang" of Japanese drama, then Noh

surely

is its "yin" counterpart.

|

Noh drama, it is

said, originated with simple Unlike Kabuki, Noh plays are

performed on

popular

folk dances and plays that were performed

at

Shinto festivals to pray to the gods for

abundant harvests and to give thanks after

the harvest.By the fourteenth century, these

simple performances had developed into

symbolic

dances performed at the imperial

court in Nara.

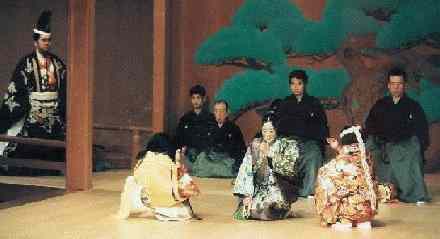

an almost bare stage, open on

three sides, simple

and plain having neither

a curtain nor background

scenery except for a

pine tree painted on

the rear

wall.

|

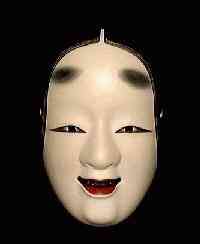

Two actors usually perform on stage, the There

may also be two or three minor characters

protagonist, who is frequently the spirit of a

person tied to this earth by worldly desires but

longing for salvation and his assistant; both are

elaborately costumed

and wear masks.

and

there is always a chorus, kneeling on the

right side of the stage, reciting the

narrative

and describing the changes of

scene. The

musical accompaniment is not music

in the

western sense, it is pure sound

provided by

three drums and a

flute.

|

The plays are usually brief and several short

dramas are performed at a single sitting.

Interspersed between the Noh dramas are

comic

skits known as "Kyogen ("crazy words")

which

offer burlesques of feudal society

and

provide comic relief for the unremitting gloom

that pervades nearly all of Noh. The broad and

slapstick humor of Kyogen often

depicts clever

servants outwitting their

samurai masters.

|

Buddhism, for in all of the Noh plays,

there is not one where a priest does not

appear to lead the ghost of a fallen warrior or

a lady in distress into the blessings of Nirvana.

|

The principal actor's movements and gestures,

however minute, are highly stylized, formal and

carefully

measured. Mime constitutes an important

part

of the drama; feelings are expressed in

symbolic gestures and movements. The

manipulation of a fan can symbolize falling

leaves, rippling water or a rising moon;

weeping

is expressed by raising a hand to the

eyes.

|

The aim of Noh is to express a desire or yearning, Although not specifically Zen

inspired, one Noh, although it cannot be

described as a popular Noh in a way is like a fermented bean concoction

not for beauty, but for the beauty we dream. The

worth of the play then depends less upon the truth

or moral, but

upon the total effect of the beauty

produced

- poetry.

observer has noted that Noh

offers an excellent

example of the highly

refined and disciplined

spirit of Zen

aesthetics.

art among the Japanese

people as a whole, does

have its supporters

who, attend the theaters as

connoisseurs with

script in hand, following the

actor's every

movement and word. I have

attended Noh

performances but must

admit that I prefer

Kyogen and

find them a welcome relief!

("natto") that some Japanese simply love

while

others prefer to simply leave.

|

~NEXT~

~NEXT~